The book that made Adam Smith turn in his grave

On ownership, control, and the rise of short-term thinking in business

'Businesses exist to create value for shareholders'.

This was the first slide of the finance 101 class I took in business school. I ate it up, not really sure what it meant. I come from a technical background and felt very much like a kid in a room full of grown-ups, and while the sentence sounded nebulous, I liked the idea of creating value. I felt like I was finally growing up too and getting ready to contribute to the world in a meaningful way.

The professor quickly moved on to more complex concepts and I felt more and more out of my depth as the consultants and finance people in the class stifled yawns.

It's interesting how big, hairy concepts can be taught as if they're universal law and just part of how the world is just naturally supposed to operate. I certainly didn't question any of what I was taught and just gobbled it all up. Afterall, if it was said by an eminent finance professor, then it must be true.

But the whole shareholder value concept has been standing on shaky grounds for decades now. Its path was a long, meandering, and oftentimes tortuous one before it could be thrown offhandedly into the first slide of an introductory finance class as if it had emerged fully formed out of the natural order of things, ready to be absorbed by gullible business students like me.

In fact, this very concept caused quite the uproar in the world of business in the early 1930s.

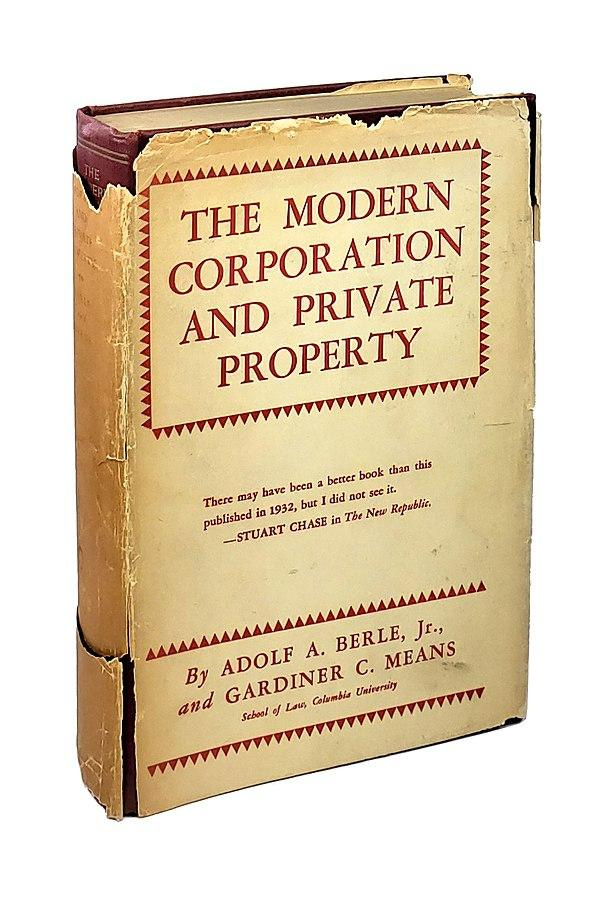

A lawyer, Adolf Berns, and an economist, Gardiner Means, cowrote a book titled 'The Modern Corporation and Private Property'. John Kenneth Gailbraith, an economist, diplomat, intellectual and advisor to multiple american presidents, went on to say that it was one of the most important books of the 1930s.

But the book almost didn't make it into the world. Shortly after being published, it was abruptly removed from circulation by its publisher, which was owned by an advisory company whose big client was General Motors. One of General Motors' managers had been horrified after reading the book, and General Motors had pressured the advisory company to pull the book off the market.

Fate would have it that this sudden withdrawal from the market piqued the bigger publisher MacMillan's interest, which promptly re-published it, garnering even wider distribution for it as a result.

But what exactly was in the book that caused such a stir as to get the first edition banned?

The shareholder vs. the owner

The book lays bare an incongruency of the capitalist economy that its supporters had been defending for almost 3 centuries, namely : what are the responsibilities of the shareholder towards the company whose shares he holds?

Afterall, an owner in the true sense of the term takes care of her assets. When we think of ownership, we think not just about the ability to enjoy the thing that is owned, we also think of a sense of responsibility towards the thing. A dog owner, for instance, has to feed her dog, take care of it, and when it dies, bury it.

But what of the shareholder? A shareholder holds none of this responsibility. He becomes the owner of a share, not of a physical asset, but of a piece of paper devoid of the responsibilities attributed to a traditional owner.

The new owner is unattached, unlike the 'old' owner, who is bound by his asset. Ownership becomes immaterial, fluid, fractioned and can be bought and sold at a whim. Ownership is split amongst thousands, which allows for massive companies spanning the globe to exist, and in this new configuration, traditional owners morph into not just investors, but speculators.

This new ownership is split between a form of passive involvement of the shareholder and an active power of management (non-owners) to influence the day-to-day operations of the business. So on the one hand, ownership without control, and on the other, control without ownership1.

The Invisible Hand is broken

By questioning the responsibility of the shareholder, Berle and Means were in fact tackling head-on the very foundations of capitalist thought which had been dominant for the past 3 centuries.

This dominant thought being, of course, the famous 'invisible hand' metaphor introduced by Adam Smith which ran like this: under capitalism, it doesn't matter if owners are selfish, because, as owners, they have a vested interest to work as efficiently as possible for the long-term good of their property; this ultimately means taking care of workers and assets, as doing so clearly is in the best interest of the business. As a result, this business efficiency will create wealth which will trickle down to everyone in society in a rising tide lifts all boats type of way, independent of the motives (self-motivating or not) of the owner.

Adam Smith's ENTIRE argument rested on the fact that ownership and control were held by the same people, not by two different classes of people, i.e. shareholders on one side and managers on the other.

This was seismic. Since then, neoliberalists have worked incredibly hard to deflect the existential crisis brought onto modern capitalism by Berle & Means, and to make sure that managers understood that what was really important was making shareholders happy. Now that those who owned the business world and those who managed it were different people, it became paramount to ensure that both parties were as aligned as possible in the interests of capital.

At the same time though, because the shareholders had switched from long-term thinking to making a quick buck, this only accelerated the obsession with quarterly results that's so prevalent today, to the obvious detriment of real value creation.

I think it's high time we revisit Berle & Means, and finally have the conversation that's been successfully avoided all these years.

As for me, I'm deciding to shorten that sentence I was taught over 10 years ago to 'businesses exist to create value'. Period.

‘La Société Ingouvernable’ by Grégoire Chamayou

This is right on the money, which Milton Friedman took to another level of economic stupidity. Michael Hammer then drove another nail into the economic coffin with his Re-engineering work. We need to move away from a profit-centric economy and establish a value-based initiative from which everyone benefits.

Great read and a timely reminder of the contingency of much of the entrenched beliefs in our current political economy. The lack of historical context that surrounds the current economic status quo really feeds these narratives too.